Getting Unbiased Answers

3/17/25 / Jane Klinger

Clients often come to us to answer strategic questions, like “How effectively are we serving our community?” or “What do residents think of our new program?” To answer these questions, we need to assess people’s attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. But answers like these aren’t static, like books just waiting to be pulled off the shelf. The way people answer depends on the way you ask the question. This can introduce bias.

Take a simple question: How would you rate the park closest to you? If you just listed your favorite features, maybe 8/10. If you just rated the awe-inspiring Central Park, maybe only a 4/10 by comparison. If the person asking has a vested interest, maybe you downplay your concerns. If you’re fatigued and answering questions quickly, maybe your evaluations are more extreme. In short, the answers depend.

In this blog, I share a few guidelines to minimize biases like these and maximize clearly interpretable, accurate results.

1. Limit unnecessary information

What you convey to participants through your study title, description, and even the style and branding of your invitation can cause unintended differences in results. Consider, for example, if you will get equally honest evaluations of your organization if participants are aware that your organization is the one conducting the research.

The study description can also create what is called “demand characteristics,” where respondents’ awareness of the study purpose creates unintended bias. In one study, for example, two groups of female participants reported their physical and mental health for eight weeks (AuBuchon & Calhoun, 1985; see also Olasov & Jackson, 1987) and one group reported worse symptoms during their premenstrual and menstrual phases. The only difference between the groups? Those with worse symptoms had been told of the study’s interest in menstrual cycle symptomology. Knowing the focus of a study can influence results in many untraceable ways—it could change what participants are aware of in the moment, create vigilance or reactance, etc.—so be thoughtful about what participants need to know and do not need know ahead of time.

2. Watch for biased or complex question writing

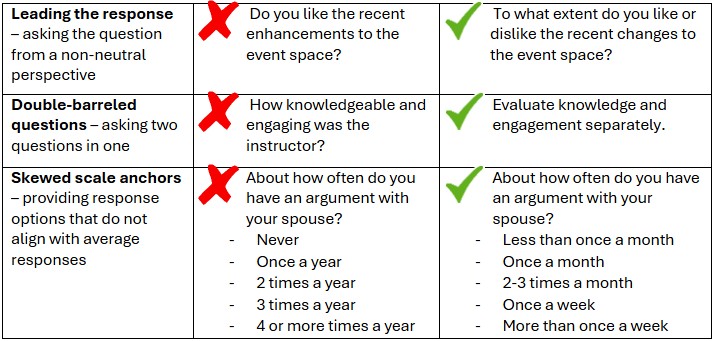

Below are a few common mistakes when it comes to designing questions and (for surveys) designing response options.

Each of the above can influence responses in unintended ways. Leading the response often causes more agreement than a neutral question would. Double-barreled questions can lead to confusion both with answering and interpreting responses. Skewed scale anchors can make people feel like outliers and defensively interpret the question differently, e.g., “they must mean really serious arguments.” Ideally, the midpoint of the scale is roughly the average expected response. (Fun fact: I use the example of marital conflict because skewed scales like this are used intentionally in social psychology research to manipulate relationship concerns.)

3. Be thoughtful about question order

Question order matters too! In one famous study, researchers approached people on either a sunny or rainy day and asked them to rate their life satisfaction (Schwarz & Clore, 1983). People reported greater life satisfaction on sunny days, suggesting that transient sources of positive or negative mood can bias overall ratings of life satisfaction. However, when asked to first report the weather and then rate their life satisfaction, life satisfaction was no longer dependent on the weather. It appeared participants corrected for the weather bias once made aware, e.g., “I feel a little down right now, but that might be partly the gloomy weather.” Even an unassuming question about the weather can affect subsequent responses.

This dynamism is important to keep in mind, especially when deciding where to place questions about overall awareness and perceptions. You may not want to ask about overall perceptions, for example, right after several questions about specific concerns.

Research design is an art, and all approaches involve some trade-offs. A skilled researcher can anticipate and minimize biases and limitations in your design, like the ways modeled above, but equally importantly, be clear about the power and limitations of the design you choose so you can interpret your findings with confidence.