Create Your Organization’s Learning Agenda

12/10/23 / Paul Collier

This is the second in a three part series on how you, as a nonprofit leader or contributor, can maximize your organization’s existing data assets. The first article in this series explored the foundational piece of this work – building your team’s data literacy. Once you’ve built your team’s data literacy, creating a learning agenda is a good next step.

Building a learning agenda can be done as a stand alone activity or as part of a theory of change process – I’ve seen nonprofits do both. There are three key elements to building a learning agenda: prioritized learning questions, possible learning activities, and the learning products or data products that result. I will dive deeper into these processes below.

1. Prioritized Learning Questions

Creating and then prioritizing your organization’s learning questions should be done as a leadership team (bonus points if you consult some of the individuals you serve or involve other stakeholders). Keep in mind that, while this starts out as brainstorming, your ultimate goal is to distinguish which questions are important to answer quickly (e.g., within the next year), which are longer term, and which are another three to four years away from being answered.

The first step is to define your learning questions.

Initially, you’ll want to define the scope of your learning agenda – is it examining an activity, a program, or the organization as a whole?

Then, if your organization has already defined its theory of change, you could ask:

- “What assumptions are we making about how change happens for our clients? What questions do we still need to answer?”

Or, if your organization has not yet defined its theory of change, I would suggest asking something like:

- “What are the three most important questions that, if we answered them, could help us make a greater impact in our client’s lives with the resources we have?”

From here it is a brainstorming activity

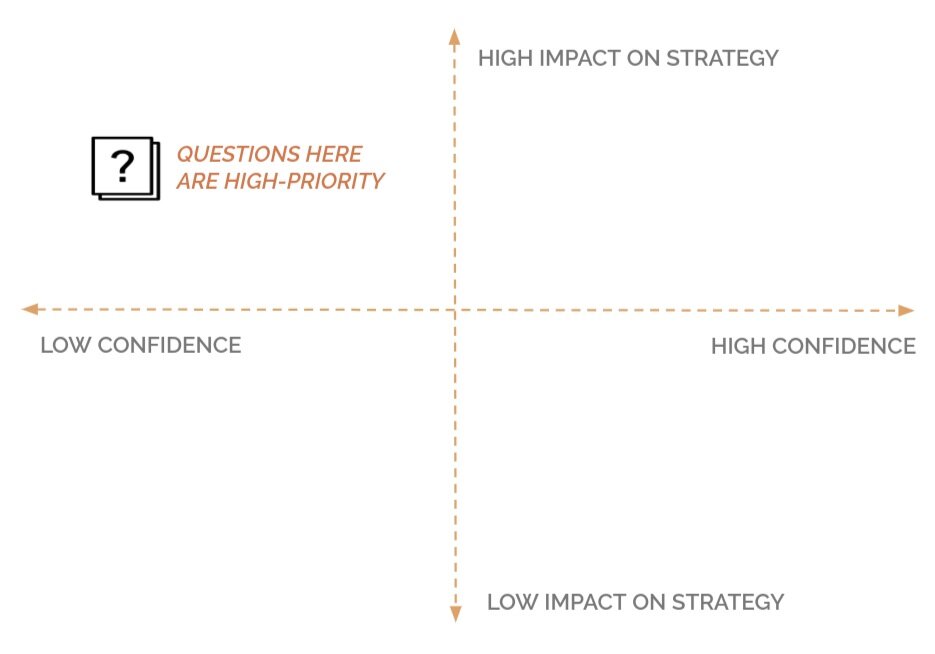

This can be done with sticky notes to encourage your team members to think independently first before coming together as a group. Then, your team can begin prioritizing the questions. Overall, your team should consider which questions are a good use of time, effort, and money to answer. One way to look at this is to consider the impact each question has on your strategy and what level of confidence you have in your answer to that question now. Questions that are most interesting and relevant to answer are ones that have a high impact on strategy and where you do not have confidence in the answer. Plotting the question on a chart like this could be helpful:

In thinking about impact on strategy, some questions that might come up in your team may be very strategic – important to how your organization creates impact – while others may be very procedural – important to the day to day work but would no longer be relevant if your organization changed its strategy. Prioritize questions that impact the strategic direction of the organization.

- An example of a question with lower impact on strategy: “What are the most effective communication channels for our case managers and our clients?”

- While this is an important question, answering it does not change the nature of what the organization does. It would be comparatively less strategic than a question like, “Should we continue providing case management to low-income families, or would increased direct cash assistance meet their needs more efficiently?”

In addition, some questions have been researched and answered extensively by others, so your organization is confident in those answers. Prioritize questions where the answers are not known.

- An example of a question that an organization might have high confidence in: “Are home visiting programs effective?”

- I have clients that provide home services to young parents with children. There is extensive research that says home visits to parents can be effective to a child’s first few years of development. Thus, we have high confidence in the answer to the question because a significant amount of relevant research already exists.

I often structure brainstorming sessions with clients using an exercise like the one outlined below. After your team brainstorms these questions, and you see the results, the next step is to think about the timeline in which you’d like to answer the questions. Remember that not all questions need to be answered in the next six months to a year. Creating an organized and sequential process will help you avoid feeling overwhelmed.

2. Learning Activities

Learning activities are the approaches you use to answer your learning questions. I like to break learning activities into two categories – 1)looking out versus 2)looking in.

The best practice is not to use only one approach but to use multiple methods to balance out the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. There are also different levels of sophistication and rigor within each approach. A survey could take the form of an expensive controlled study, or a quick questionnaire through a tool like Survey Monkey. Higher levels of sophistication and rigor generally provide greater confidence in the results, but the tradeoff is additional money, time, and effort. Remember that you can start simply and add in complexity over time.

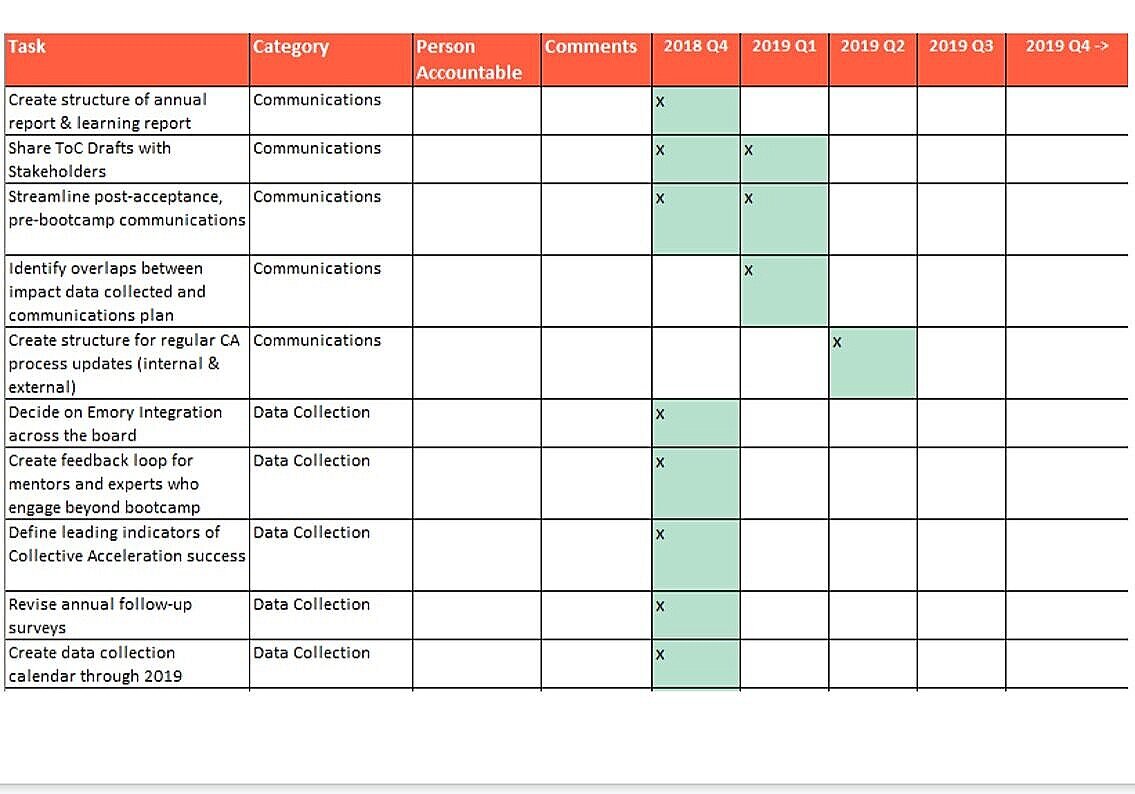

The next step is to schedule the learning activities. What month/week/quarter will you tackle which questions? Who is accountable for each of these learning activities? One nice visual way to schedule out learning activities is creating a Gantt chart, which answers what, when, and who does the work.

3. Learning Products/Data Products

The final consideration is how to share what you’ve learned – these are your learning products. There are different communications channels through which you could share what you’ve learned. Sometimes emails or newsletters are effective methods to share information because you already have scheduled communications going out on a regular basis. Or, maybe your organization has a blog, which would be a great medium to share the results of your learning activities.

Some common ways to share what you’ve learned include:

- Emails

- Newsletters

- Webinars

- Infographics

- Blogs

- Posters

- Project-Specific Reports or Evaluation Reports

- Your Annual Report

Whichever approach you decide to use, sharing your findings (even at a very high level) can be helpful for external parties, such as other organizations doing similar work, and internal stakeholders, such as staff or board members. Codifying your learnings in some sort of product also serves as a reference for anybody new who is joining your organization. Finally, a learning product can help you show the individuals you collected data from what came out of your project, which shows them you thought their perspectives were valuable.

In my next blog, we will investigate a third strategy for maximizing your nonprofit’s existing data: Conducting a Data Audit.

This post by Paul originally appeared on the Coeffect.co website.